If you’ve ever wondered “is Iceland part of the European Union?” then you won’t be alone. It’s a question we’re often asked and the answer isn’t quite as straightforward as you might think. Let us explain a little about the EU and Iceland’s relationship with it.

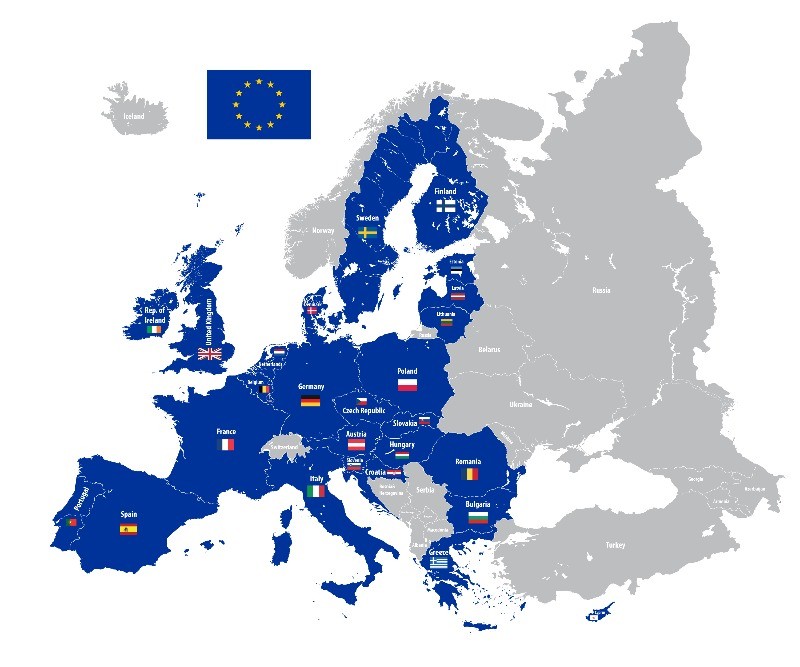

European Union Countries

Those that currently hold EU membership

As of May 2020, the countries that are a member of the European Union are these: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Republic of Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the UK. Of course, the UK’s position could change if the Brexit process that was begun with 2016’s referendum is completed.

Is Iceland part of the European Union?

Iceland isn't in the EU but is linked via the EEA Agreement since 1994, fostering close historical, political, and cultural ties with Europe. You’ll notice that Iceland is missing from that list, as are Norway, Switzerland, and a handful of other European countries that you might expect to be included.

Relations between Iceland and the European Union

Although Iceland isn’t a member of the EU, it is a member state of a number of other associations and alliances. The nation is part of EFTA, the European Free Trade Association, with Norway, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein. This runs alongside the European Union; all four countries participate in the European Single Market. In other words, the free movement of goods, services, capital, and labor is permitted between Iceland and each member state of the EU.

Is Iceland part of Schengen?

Yes, In addition, Iceland is a signatory to the Schengen agreement, along with Austria, Poland, Lithuania, Czech Republic, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, Denmark, France, Germany, Malta, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Hungary, and Sweden, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and Norway. This important piece of legislation was originally passed by five of the member states of what was then the European Economic Community in 1985. Under the terms of the treaty, internal border checks were pretty much abandoned, encouraging international cooperation and trust.

Five years later, the scheme was widened to facilitate a single visa; in simple terms, if someone is issued a visa by a Schengen member, they can travel to any other Schengen country without the need for an additional visa. Iceland, despite not being a member of the EU, signed up for Schengen in 1996 (The UK and the Republic of Ireland, though members remain outside the Schengen zone.)

Iceland and the European Economic Area

Iceland is also part of the European Economic Area, a commercial agreement that links EFTA and the EU. It also maintains close ties with the other Nordic countries as part of the Nordic Passport Union. As a signatory, Icelanders can travel to and reside in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland without the need to show a passport. The EEA agreement and Iceland’s links to other Nordic countries are crucial to its economic success, but as it’s not a member of the EU, it has no voting rights and therefore no say in policymaking by the EU parliament.

Icelandic European Union Membership Referendum

Actually, Iceland did submit an application to join the EU, back in 2009. Back then, things weren’t going so well for this Mid-Atlantic nation. Their problems began late in 2008, but to understand the causes, we need to go back a little further. Three Icelandic banks, Landsbanki, Glitnir and Kaupthing had grown considerably. It had been easy for them to secure credit from the money markets. But as the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 gathered momentum, investors began to get a bit jittery and confidence in those Icelandic banks faltered. The Icelandic króna weakened, inflation rose and the country’s debt grew to more than seven times its GDP. Things were a little dicey for a time. Some thought the answer to Iceland’s problems might lie in adopting the euro, but to do so, they would first need to become a member of the EU.

Despite its financial woes, Iceland still met the EU’s criteria for entry: politically stable, a democracy with a strong human rights record. Because of Iceland’s position, it already met many of the EU’s economic criteria and though there were a number of issues that might present a challenge, particularly with regards to fishing and whaling, at the time it was expected that Iceland’s application could be fast-tracked with entry into the EU, perhaps as early as 2011. The Icelandic parliament was divided. After lengthy discussions, the Alþing voted in favor of accession talks; it was a close vote with 33 in favor, 28 against, and 2 abstentions. Nevertheless, it was a majority and under Icelandic law, the application for Icelandic membership could be submitted to the EU by the Icelandic government in July 2009. The groundwork had been set for the country to join the European Union.

Iceland and the EU - Withdrawal of Application

So what happened? Clearly, things didn’t go according to plan.

That’s correct. Things didn’t quite work out as some had hoped. At first, all went well. A number of EU member states announced that they were happy for Iceland to join, among them Lithuania and Malta. The Icelandic government completed a series of 2500 questions sent to them by the EU Commission. A negotiator was appointed.

But then Iceland’s financial crisis and, particularly, the Icesave dispute, reared its ugly head. The privately-owned Landsbanki had been placed into receivership in autumn 2008, one of three important financial institutions to go bust in a short space of time. Investors from the UK and the Netherlands lost €6.7bn of savings, for which their own governments had to stump up to bail them out. The Icelandic state couldn’t and wouldn’t take on this financial burden. The British and the Dutch argued that they should repay some of the debt.

Though both nations weren’t officially blocking Iceland’s entry, it was expected that the Icesave dispute would need to be resolved before formal membership could be agreed upon. Formal negotiations began later in 2010. Progress had been made with the Icesave dispute but fishing and whaling issues had yet to be resolved. And remember, Iceland was keen to secure EU membership as that would enable them to join the euro, seen at the time as a far stronger currency.

As time went on, political opinion began to turn. By the end of 2012, Iceland was getting cold feet. With time to think, some felt that joining the EU might not be the solution it was once felt to be. Financially, the country was in much better shape. The global economy was starting to pick up and Iceland’s fortunes were improving. Unemployment fell, investment rose and Iceland’s government got to work reducing some of that once crippling debt. The króna had recovered some of its value and there was less urgency when it came to adopting the euro instead. Perhaps it was prudent to buy some time. There was a growing consensus that Iceland didn’t need to be a member of the EU to survive after all. Maybe it could continue to go it alone, interacting with Europe on its own terms.

Does Iceland use the Euro?

No, Iceland does not use the Euro as currency. The official currency of the country is the Icelandic Krona. However, you may be able to use Euros in certain shops and retailers. Make sure to ask first though!

EU Membership Negotiation with Iceland

Many wonder why Iceland isn't part of the European Union. Iceland hesitates to join the EU due to concerns about its vital fishing industry, fearing negative impacts from the EU's Common Fisheries Policy.

A proposal was tabled to suspend negotiations with the EU and early in 2013, it was adopted. Both the Independence Party and the Progressive Party stated that they wouldn’t support the admission process unless the Icelandic people had been given the chance to express their views in a referendum.

Meanwhile, the Social Democratic Alliance, Bright Future and Left-Green Movement reiterated their support for joining the EU. In the April 2013 election, the Progressive Party were the big winners, forming a coalition with the Independence Party. Davíð Gunnlaugsson, then Iceland’s youngest ever Prime Minister and at the time chairman of the Progressive Party, was adamant his country was better off without EU membership.

A change in thinking

In June 2013, the Icelandic foreign minister informed the EU that the new government was placing negotiations on hold; by August, the negotiation committee had been disbanded. The official letter withdrawing the Icelandic application to join the EU was sent in March 2015. However, it was sent without the authorization of the Alþing, leading the EU to suggest that Iceland’s application hadn’t formally been taken off the table. But just because the powers that be at the EU thought it would still be a good thing for Iceland to join them didn’t mean that everyone in Iceland had to agree with them.

Iceland support of the EU Negotiations - Public Opinion

And with another change of government in 2017, things looked even less hopeful. At least two-thirds of the MPs elected to the new parliament opposed EU membership. In 2018, Iceland’s Prime Minister Katrin Jakobsdóttir rejected the idea of reopening EU negotiations. The polls indicate that the population supports her. In October 2018, the Iceland Monitor reported that 57.3% were opposed to EU membership and went on to say that most Icelanders have rejected EU membership in every poll published since 2009.

The EU’s focus on the UK and its Brexit process has taken the spotlight off Iceland and allowed it to consider its future without scrutiny or interference from Brussels. For now, at least, Iceland is happy to remain outside the EU.

By

By